Your Magic is a Joke

A Warning To Comedians

Magicians aren't strictly comedians. But we do love to study what they do and learn from their performances. No one chastises a magician because he or she analyzes what makes a magic trick work. I could even make a case for how it's impossible to reach the purple heights of our art by not paying attention to what produces a sense of awe in our audiences.

But comedians are a different breed. I know a few that consider it a comedy sin to deconstruct a joke. My research points to E.B. White and his wife Katherine as the originators of this somewhat famous batrachian simile paraphrased here:

I've heard this quote from the mouths of some famous comedians like Jimmy Carr (that I mention later). I don't think that all comedians detest, hate, or avoid analyzing what makes something humorous. Maybe the natural comedians out there want to keep the humor from becoming formulaic.

Who knows?

All I can say is that if you're the type of person who hates analyzing comedy, this article is not for you. But if you're like me, and you feel a bolt of pride at hearing the words, "Dude, you think way too much," then read on. You should feel right at home!

Introduction

I hear the laughter. It follows the climax of an effect. At the end of my opener, I grab two handfuls of Eisenhower dollar coins from the air and let them cascade into a clear, glass goblet. It's the crescendo to a Miser's Dream-type routine. As I spread my hands apart and adopt the "applause cue" position, the audience is happy to comply. But along with their clapping, I hear peals of laughter.

But the magic wasn't funny.

My opener is two minutes of "eye candy" for the audience. I perform it silently while a driving cello instrumental thrums out a cadence.

And there's nothing funny about it. Which makes it entirely at odds with my performing character for the rest of the show. The Jafo that performs in front of the audience tries to be fun, a bit silly, absurd at times, and rarely no-nonsense. But if you watch my opener, you would never know what kind of character is in store for the remainder of the show.

It's not a funny opener. And yet I hear laughter. And not just at the end. Laughing punctuates a few of the magical moments along the way. As for the rest of the show, there's a lot of laughter. Most of it happens in the places I want it to be - fortunately for me.

But why does it happen at all after a magical moment? Why does laughter so easily accompany astonishment?

Because your magic is a joke.

Definitions

But clearly, I must be using some nuanced definition for the word joke, right?. Well, perhaps. The dictionary describes a pretty common usage that covers most cases.

And this sounds pretty on-point for most cases. But I do reject one key concept here. A joke is not always "done to provoke laughter." This phrasing introduces the goal of invoking laughter. That goal may or may not even exist. Can we have an unintentional joke? Sure! Some of the best ones happen by accident.

I would slightly alter the phrasing: "Something said or done that usually provokes laughter..." I say usually because some jokes aren't intentional. And some aren't even funny! And the word usually does not smuggle in intentionality that isn't warranted.

That's an improvement, but can we do better? Absolutely, we can. The definition I pulled from the dictionary can only describe a joke in terms of something that invokes laughter. This description is useless when trying to understand why the joke is funny. If we simply say that a joke "is that which creates laughter," then we have no hope of explaining why your magic is a joke. We can only say that your magic is a joke because it has created laughter. And I don't want to define the joke into existence. That feels...dishonest. And circular.

I probably can't explain it any better, but I know someone who can. Jimmy Carr is an English comedian and television host. I know comedians loathe deconstructing humor. But thankfully, Carr has deconstructed jokes as the joke itself. And from that, we get some valuable observations.

Carr's Definition

Let me first give Carr's full quote some breathing room here. Then I'll distill his words down to their essence. His words:

I love this. That second part is worth repeating. The punchline is the sudden revelation of a fact. And that fact has been withheld from the audience. That describes almost all magic!

We should break this down - almost every magic trick relies on the audience making false assumptions. They must do so. I like to describe my job as "leading people away from correct thinking." Try to think of a magic trick in which the audience has an accurate understanding of the entire situation.

On a side note, this is not a try-and-prove-me-wrong challenge. I hope such an effect exists. So, if you know of one, tell me! Post in the comments below. But keep in mind, my blog is outward-facing. That means no exposure. Sanitize your responses. Thanks.

The second concept in Carr's definition is worth discussing now. In magic, we reveal a fact that we have withheld from our audience. There are many labels for this: the payoff, the kicker, the finale, the revelation, and many others. A magic effect pays out at the end by revealing some fact that the magician has concealed from the audience. Again, comment below if you can think of one that does not.

Nowhere are the two concepts of assumption and revelation so firmly encapsulated as a typical cups and balls routine. The audience makes many essential assumptions about the setup, handling, and very nature of the props used. And, of course, the final load is a sudden, surprising revelation of a fact that the performer has kept concealed.

Wait a sec. You thought there was going to be a small, red ball under that cup? No way! That's a full-sized, regulation baseball!

And what reaction do you typically experience when someone is honestly taken in by a well-performed cups and balls routine? They don't just sit, glowering with folded arms. No, they clap, shout, and laugh!

They laugh because the structure of the routine fits this definition of a joke surprisingly well.

Benign Violation Theory

Now class, open your Advanced Joke Theory textbooks to page 112. I want to introduce a strange way of thinking about humor.

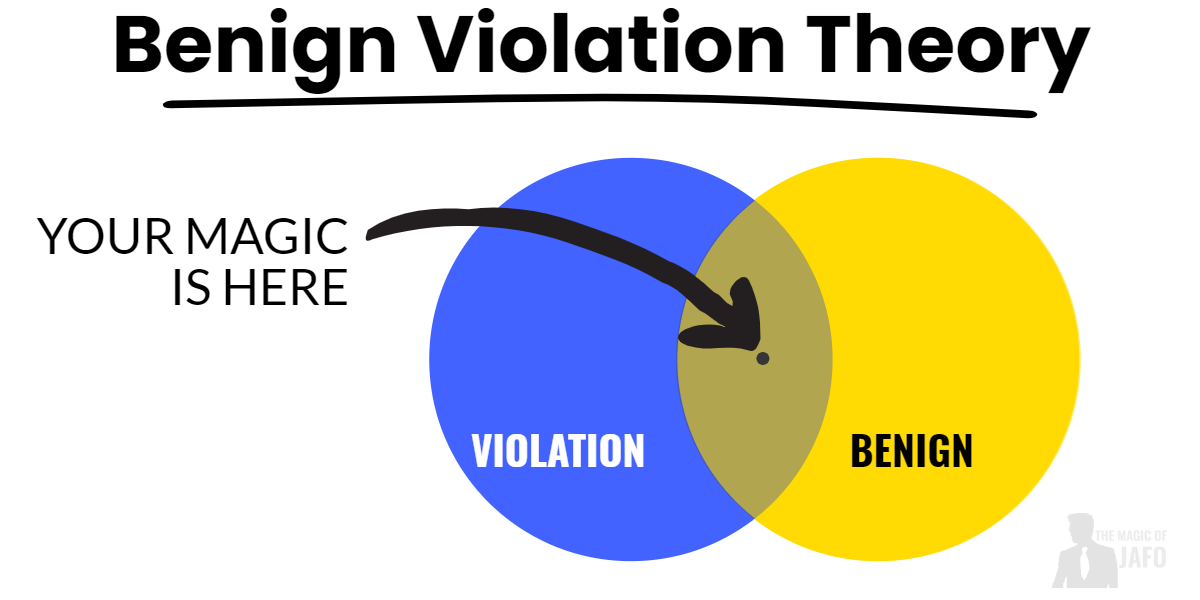

Benign Violation Theory (BVT) is the work of Dr. Peter McGraw. McGraw is an Associate Professor of Marketing and Psychology at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Together with Caleb Warren, the two have worked to integrate existing theories of humor.

BVT posits that humor occurs when three conditions are satisfied.

- A given situation is a violation (defined below).

- The situation is benign (also defined below).

- Both conditions occur and are perceived simultaneously.

An example of a benign violation would be tickling or play fighting. Either fit the pattern because each seems like a physical attack (the violation) yet is harmless (benign). The theory has the added benefit of explaining why certain things are not funny. If the violation becomes too tame or too risqué, the humor fizzles. The same happens if the violation stops being benign. We've all seen a joke go too far.

I promised a few definitions earlier. First, what does it mean to say that a violation has occurred? It's not just a physical "attack." We all have beliefs about what the world is and how it should behave. A violation threatens that belief or perception.

I think you can see the immediate correlation with magic. What is magic if it is not a violation of what is typical or expected? If an action did not violate our beliefs about how the world is supposed to work, then no magic has occurred.

We can also extend that threat to include the well-being of our psychology. We commonly know this as teasing, sarcasm, insults, and the like. But a good magic trick will attack our psychological well-being. Magic becomes a violation of what is normal or even possible.

But it's not just the violation itself that needs to occur. The "attack" must be perceived as benign - it must be thought of as safe by the participant. It needs to be accepted. Have you ever performed a magic trick for a person who turned belligerent? They did not accept the violation. The attack was not benign in their eyes.

That's why the third condition needs to be met. Condition three simply says that conditions one and two must exist simultaneously in the mind of the audience.

When a person shows a solid ball in one hand that suddenly becomes two, our perception of what is possible has been severely violated - but benignly. Such a combination, when performed skillfully, can almost guarantee laughter.

Conclusion

So what's the use of analyzing the laughs? Can't we just enjoy it? Well, knowing why someone laughs at a joke or a trick shouldn't diminish your enjoyment of that connection. The audience certainly won't mind that you've probed deep into their psyche. But perhaps with an understanding of what causes laughter, you can have more control over when it occurs.

As I cautioned in the opening, breaking down a joke isn't everyone's idea of a fun night. But if you're just a smidge as analytical as I am, it can be a fun exercise.

Can you produce a laugh when there wasn't one before? Is there a magical moment that is supposed to get a gasp when it gets a laugh instead? Comparing magical timing to comedic timing unlocks new vaults of performance gold that were once locked away from you.